The mayor and his wife take us to Gasthaus Wolf for lunch, which is the big meal of the day in this part of the world. Businesses open early (typically 8:30am), close from Noon-3pm, and reopen from 3-6. People eat a big meal at lunch, then take a break. Dinner or supper is usually a lighter meal.

After lunch, with the mayor and his wife (who is doing all the translating now), we go exploring. We see what's left of the trenches that were dug during the war. Portions still exist, deep channels running through the woods and fields. We learn that local townsfolk were also forced to help dig the trenches. My father remembers seeing locals walking along a parallel road carrying farm implements. He always thought they were going to work their fields. Now we know they were also forced to help dig the trenches. In effect, they were slaves too. Also with the mayor's help, we will identify the place where Apu believes he spent the last

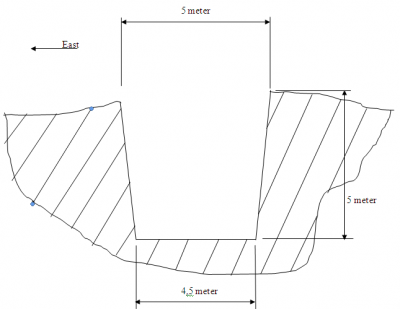

Cross section of the trench we had to dig.

Looking south direction, east is on left and west is toward right.

According to the records in the archive – by Mr. Schober’s summation – the length of trench we created was approximately 1800 m. And that length will fit in with the volume of dirt we had to move. The sketch in the above shows the cross section of the trench. In February and March, with wintry soil condition, a group of 10 laborers had to complete 1-meter length of trench every day. We were working on that stretch of Panzergraben for 60 days.

Over 60 years the ground rehabilitated itself and only a short, partially filled segment remained for a reminder. The photograph fixed this reminder for future viewing.

2. The camera is looking due south, therefore left is east.

I descended into the ditch on my free will. I felt differently than in 1945, while hauling out the dirt to create the ditch. I felt the freedom.

With the mayor and his wife, we explore the fields where the "infirmary" barracks used to be. There are basically two sections where there were barracks: one is called the Hölle (German for hell) the other is named Schuffergraben. The Granite Barracks were in the Schuffergraben area. We are shown several spots where the locals discovered mass graves. Today, corn is growing in these fields, which are oh-so-close to the border with what is now Slovenia. We visit the border, which is mostly unguarded, and cross freely back and forth over the border. A few days later, while driving by the same spot, we notice guards at the border. It's an intermittent thing. Freedom has come to this small corner of the world...part time.

In one cornfield, the mayor picks up a red brick. He explains that whenever the field is plowed, the plow kicks up one or two bricks buried in the dirt. The brick is believed to be from the foundation of one of these infirmary barracks, perhaps the one my father was in, perhaps not. But certainly from one of the buildings used by the Germans at that time. The locals called this "the granite barracks," because of that stone foundation. We break off a piece of that brick to take home.

Here at the cornfields I have realized that the infirmary barracks was the compound of the so-called Granite Barracks. We also learned that the late afternoon the day of liberation the bluish colored larger building was dynamited, blasted to the ground and the wooden structures were torched. The flames were visible in the early evening and the smoke; odor from the burning buildings was very much felt in Aigen, which is less than 2 km away.

Here at the cornfields I am recalling from my memory of the events that put me in to the “Granite Barracks”.

Toward the end of March, 1945 about 40 of us became ill with typhoid (Fleck- typhus) and we were separated from the rest of the company and walked to an another barrack, out side the village of St. Anna am Aigen. We were walking and every one of us had a buddy, a comrade or two helping us along to our destination. Gyuri was my buddy, my comrade to help me. (For additional details please see the chapter entitled GYURI.) South of the village some distant away we arrived to a camp mostly consisting of wooden constructed barracks. The barracks were empty and we the sick became the new tenants. The barracks were occupied before but was orderly when we took up residency. We didn’t know who the occupants were before. We were left there to die. We were not guarded (there was no need for guard anyway, we weren’t any condition to run away), not supervised, not medicated and not fed. I remember once I was toasting some moldy bread and eat it. I don’t know where the bread came from. Also I don’t remember who kept stoking the fires in the small potbelly iron stove. And just the same, I have no idea of who removed the dead bodies in timely intervals, as they were not alive any more. People were dying left and right.

Late in the afternoon, of the fourth of April, I vividly remember that lying on the bunk bed and looking out the window, I saw a German soldier was busy setting up a machine gun on the “parade ground” in the meadow. I knew that the machine gun would be aimed at us, the sick Jewish Laborers. By that time it did not faze me a bit. Then another soldier came on a bicycle, they had a very brief discussion and the first soldier packed up his machine gun and both left in a hurry. Next morning we found ourselves liberated by the Red Army. I was liberated in total stillness. Nobody announced that we were free. No living soul came to our compound to announce anything. On the other hand, our camp consisted of a couple of wooden barracks with a number of dead bodies inside. Also some people actively dying and in their last hours or minutes before taking their last breath. And may be 6 – 7 of us were still alive. Barely alive. The Red Army passed our barracks either during the night or early in the morning of April 5. They passed by our barracks without one single gunshot. I got up in the morning, just the same as the previous mornings. Went outdoors. And in the distance, near the road, I saw Russian solders leisurely strolling by. The time could have been between 7 and 8 in the morning. I told this new revelation to others. I had to get up and go. Go home! Do not waste any more time! I immediately formed a small group of 5 comrades and left the infirmary compounds and headed east, toward Hungary.

I said: barely alive. Ten days later, on April 15, I met my father and he described our reunion in his book “Amerikai Üzenetek”:

“…And one ailing, startlingly skinny, quivering skeleton, staggered towards me: My Son!”

Here in the cornfield, the Mayor gave us a piece of brick. One piece of brick from the many pieces are scattered around. A piece of brick, a physical evidence from the Granite Barrack. And with that piece of brick, Mayor Weinhandl handed me a psychological liberation also.

Here at the cornfields I saw the topography of the field and realized that the infirmary barracks was part of the so-called Granite Barracks.

Here at the cornfields I was standing very close to ridge, which was on the edge of the horizon in my sight of line from the bunk bed. The ground was flat where we were standing and the north – south road was running about 50 meters west from us. Therefore I could not possibly see the road from my place of the bunk bed. The window of my barrack building was about 15 meters below the level of the ridge where we were standing. But the Germans knew that was their getaway road.

On the 5th of April 1945, probably less than 20 laborers were still alive in various serious ends of life conditions. How many survived the day? How many died within hours after the liberation? I couldn’t tell. But here on the cornfield I “saw” the Granite Barracks and from the compound we were heading south and after a short distance, may be 100 – 120 meters, made a left turn to the road and heading east. We walked on foot. We walked to approximately ‘till 4 or 5 o’clock in the afternoon. The total distance we covered was about 3 km. Yes, three kilometers. It was a huge accomplishment for a day’s worth of walk. And that describes our physical condition for that day. Then we found a company of Russian soldiers camping there. They had kitchen and field hospital. A Russian intelligence officer interrogated us. The intelligence officer was very friendly, gave us advise and instructions as to what to do and how can we reach our goals to our home cities. Then we were fed and provided place to sleep. Next morning, after breakfast and with food packages in possessions we were on our way to reach the railroad line, which brought Russian war supplies to the front. To recap: On the 5th, walking 3 km, sleeping in Russian encampment. On the 6th, walking may be 5 km, sleeping under the stars. On the 7th, walking another 4 km or so, reaching the railroad line. I never left the railroad car until we reached a station in the suburbs of Budapest. Along the way we parted from the others as they each reached a destination in their mind.”

There on the cornfield it was established that the Russian encampment was on a meadow in the next valley, east of Kramarovci/Sinnersdorf, which was just about 3 km away. By the way, Mr. Schober based on his research; he placed the railroad station 12-km away from the Granite Barracks.

“I found out that there was 1945 a railroad about 12 km away in the east from the barracks in the area "Höll" via Kramarovci - Sv. Jurij - Grad/Gornja Lendava – Mackovci” – Mr. Schober informed me.

Here at the cornfields I repeated the steps I had made on the morning of April 5 1945, when I was started to walk east, toward Kramarovci, toward Hungary. And on a little bridge I was freely straddling my two feet over the border marking line between Austria and Slovenia.

By now we have firmly established that the Granite Barracks were the “infirmary” where I spent the last few days of as slave laborer. But were did we reside in St. Anna in 1945? I searched my memory and typed the following notes: The school compound was surrounded by chain-link fence about 2 meters in height or may be a bit shorter. From a sixty-year’s distance; I am estimating that the frontage was about 35 meters long and the backside was definitely shorter. The sides running in the east-west direction were 50 meters long. And may be the southeast corner of the fence was somewhat rounded or irregular to follow the outline of the included structures. The frontage with the double swing gate was on the West Side. The double swing gate opened toward the yard and fully opened to about 7 meters, which was amply wide enough to allow two horse drawn carriages passing through the same time, one in and one out in opposite way. In the buildings within the compound the Ukrainians were housed in the classroom toward the front. The additional classrooms served as "living quarters" for the Jewish laborers. I was imagining that the kitchen was in the rooms somewhere in the back. Also auxiliary buildings and sheds were adjacent to the east and to the south side fence. Any activities between the auxiliary buildings and the fence were hidden from the general view. Gyuri and I climbed over the fence in those generally hidden places.

I am certain that people did not reside in the structures to the immediate south of the school compound. I don’t remember ever seeing anybody over there while we went on our excursions. The structures had no fence around them and it was easy to trespass. Also, the structures provided excellent cover for us in both leaving the place and coming back. Especially when we returned from our food "shopping" tours. We were able to assess the general situation in the schoolyard without exposing our presence by playing hide-and-seek among the structures. That way we were able to choose the proper timing to climb back into the compound. Sorry, but those were not the times for sightseeing. So I didn’t pay too much attention for the purpose of the neighboring building structures. But I am glad that those buildings were there and we welcomed the protection they gave us. We took advantage of the unique geographical combinations on the ground. (I have still used the “school compound” as reference name because lacking any better name yet.)

While the Mayor picked up red bricks from the cornfield, Mrs. Weinhandl was busy receiving calls on her cell phone. The time was just shortly after the student’s were dismissed from their classes for the day. To their mothers the student’s told their experiences about the today’s “history class” and my saying of THANK YOU. The calling mothers had very supporting opinions, which Mrs. Weinhandl conveyed to us.

Later in the afternoon, Mr. Schober and his daughter join us and we revisit the same sites again. Afterward, the mayor and his wife go home, while Mr. Schober takes us to Bad Gleichberg (a nearby Spa resort town) about 20 minutes away. There, we sit in an outdoor cafe and sip Diet Coke (called Coca-Cola Light in Austria) as the sun begins to set.

Our first full day in St. Anna and we have met with the school children and found the site of the infirmary barracks. One big mystery remains: Where was the barracks where Apu was housed before he got sick? He is now sure the old schoolhouse was not the place! Who knows what tomorrow will bring?